A warrior. A mage. A trickster. A guide. A tavernkeeper. And a couple hundred fired-up spectators aiding, abetting, and sometimes impeding their journey

Earlier this month, I had the great joy of attending Twenty-Sided Tavern, an officially licensed Dungeons & Dragons interactive stage show. It’s a rollicking good time, and you don’t have to be an experienced tabletop gamer to enjoy it — although I do think it helps! — because the experience is designed to teach you the basic rules of the game and framework of narrative creation as you go. Since I do play ttprgs, this was thoroughly up my alley, and I’m glad that the Instagram algorithm intuited that I would want to know about it.

The experience does a great job of capturing the madcap spirit of ttrpgs, then expanding it to take up the space of a full stage and to encompass the liveliness of the audience. Engagement begins as soon as you’re in the theater: there are some fun Dungeons & Dragons set pieces and photo ops in the lobby.

(I did find myself wishing that the concessions on offer were more themed. There are a couple of specialty cocktails, but otherwise, nothing that really felt in-world or “taverny” — nor, for that matter, the sort of things that could be a bit tongue-in-cheek evocative of the typical fare when ttrpg players gather around a table.)

Once you’re seated, the performers start setting expectations. They welcome you, give you some flavor of their on-stage persona, tell you to scan the QR code in your program to open the website you’ll be using to vote, and start soliciting your input for Mad Libs. Your program also has, tucked inside it, a sticker giving you your role for the evening: either warrior (red), mage (blue), or trickster (green). That becomes important for later mechanics.

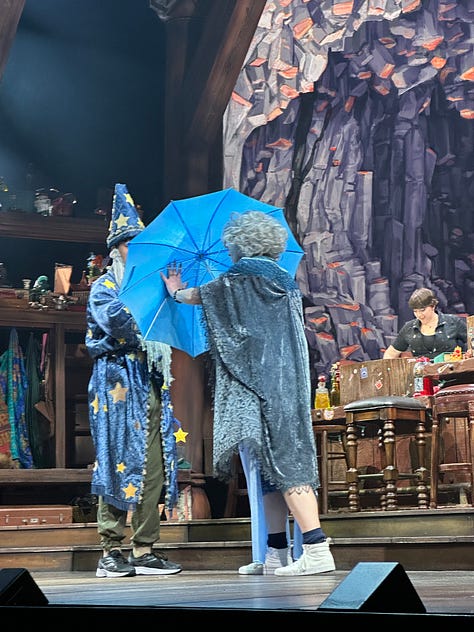

When the show gets properly going, the dungeonmaster DAGL welcomes you into the world and gives a very, very broad explanation of what, exactly, Dungeons & Dragons is. Together with the Tavernkeeper — responsible for much of the number-tracking and other logistics during the show — he explains the basics, including the importance of nat 1s and nat 20s, as well as the concept of a character sheet with modifiers. We then get to vote to narrow down the species and class of our avatar, as determined by our sticker and role. Rather than trying to educate the audience on all the options, the DM offers three choices for each. This mechanic is a great way of building camaraderie between performer and audience, immediately giving you a bond because you’ve had a say in shaping their identity for the evening. The night I was there, we ended up with a bird-person paladin who wouldn’t fly, a sex-crazed old lady mage, and a “wizard” with a secret past as an assassin.

The campaign is well-chosen, since the focus on chaos disrupting the magical weave of the world means they can introduce all manner of silliness and whole-heartedly embrace absurdity. They meet some standard D&D NPCs along the way: the barkeep, the gang of urchins, the sorcerer and their apprentice. Other choices of where to go and who to meet get made by a combination of votes and dice rolls. It’s all familiar fare, but given unique flare by the performers.

The set is a mix of digital and practical components, scattered with beaten-looking benches and stools, as well as a bar for the DM and Tavernkeeper, and shelves stocked with a variety of props for the performers to grab at will. The screen behind all of this projects backgrounds, which I found to be a nice augmentation but never a distraction, as well as the dice rolls (via cameras cleverly hidden inside lights above each performer’s dice tray), character sheets, and hit points, when such things are relevant, along with the results of the audience polls and skill challenges.

Oh yes, there are skill challenges for the audience. The roll of the dice determines a lot, but the audience has a palpable effect as well. Sometimes there’s a riddle to solve, and if not enough of the audience gets it, your performer fails in what they were attempting. Another challenge, used a few times, involved every member of a particular group having to button-mash on their screen in order to “fill up” a bar projected on the big screen — and either having to make it past a certain benchmark or, for added difficulty as the show went on, hit it between two benchmarks. We only managed that one out of three times! Those group challenges, especially by the end of the night, had the whole audience whooping and hollering.

And my gods, the cries of agony when someone rolled a crit or we failed a death save.

Because, yes, a character can die! (Although they do build in ways for that performer and their third of the audience to stay involved.) And death is not the only consequence of a bad roll — and nor is story success the only reward for a great one! Nat 1s and nat 20s also trigger the player and the Tavernkeeper to take a shot.

The audience is never left out of the action for any length of time. The DM and Tavernkeeper explain what’s happening in direct address all along the way. The Performers do most of their action down on the apron of the stage, and as I mentioned before, their rolls are usually cast up on the big screen, while occasionally, at moments of high drama, often when there’s advantage or disadvantage in play or for a death save, they come down and roll a massive d20 instead. Combat is kept short, to a single round in most cases, so that the story keeps clipping along. The audience gets solicited for shout-out contributions throughout the show, particularly whenever there’s an NPC who needs a name.

One downside of that particular mechanic is that you do end up somewhat captive to the lowest common denominator in the audience, who give “Boaty McBoatface” type names or whose sense of humor never progressed beyond repeating the most-well-known of Monty Python jokes. A little of that is tolerable; a lot of it starts to feel wearying, or at least it did to me, though admittedly I sort of burned out on Monty Python references by the tenth grade due to total oversaturation, and several years of working for a Renaissance faire lowere. YMMV, obviously. That said, the performers are very good at turning the low hanging fruit flung at them into something charming and clever, as well as building on the contributions throughout the evening so that the audience ends up with some “inside jokes” peculiar to it that will (likely) never be exactly repeated in another audience. (Ours was the curious recurring presence of Wario and Waluigi in the midst of Waterdeep).

A few lucky audience members also get brought on-stage for short periods. In one case, the skill challenge was a giant game of Jenga, played by audience representatives for the three groups. Another time, audience help was solicited so that the DM didn’t have to talk to himself as two different NPCs for an extended period of time.

The story itself matters far less than the joy brought to creating it. Everyone on-stage seems to be enjoying themselves to the hilt in every moment, their energy never flagging during the 2.5 hour performance. And that energy is infectious — I could feel it swelling in the audience as the night went on. Sure, some people entered the theatre already all-in (and yes, I was one of them), but not everyone. By the end, though, the reticence had sloughed off the stoics; the room had an electric buzz, everyone enthralled, holding our collective breath to see how the dice would fall, then exploding in either victory or defeat.

That shared experience is something I prize so highly. It’s why I love interactive and immersive entertainment, and it’s why I still evangelize for the American Shakespeare Center’s “do it with the lights on” ethos. I love feeling like I am, if only for a short time, totally in sync with a crowd of total strangers. It’s a special thing, and Twenty-Sided Tavern skillfully draws that camaraderie along.

I would definitely go again — not least to see how much changes night-to-night, not only in the story itself, but in its mood and tenor. It does tend towards broad caricature and slapstick humor, but there were some glimmers of deeper emotion. I’d be interested to see if, with an audience that tilted further in that direction, the show ends up showing a bit more heart as a counterpoint to the riotous comedy. Just a couple of well-timed, well-chosen deeper moments — moments of stillness, vulnerability, and true emotion — could create something sublime, if the opportunity was there for them. It’s not something you could force; it would have to rise naturally from the flavor of a particular audience and the co-created story — the same way that you can’t really force that in a game, but if it develops naturally, you end up with your heart in your throat and tears in your eyes. I’d be interested to know if something like that ever manifests in this show.

This show could easily develop a cult following, and I could also see it being franchised and running in cities all over the country (much like Drunk Shakespeare, which has a similar riding-the-edge-of-the-catastrophic-curve glee). I would be very interested to see Twenty-Sided Tavern mounted in some differently-shaped spaces, that bring the performers and audience together even more, like a thrust stage or something with cabaret seating to more nearly mirror the tavernesque vibes. (The traditional theatre seating in its current space does get elevated by fun lighting choices.)

Overall, I had a blast, and I heartily recommend the experience to anyone who has the opportunity to see it!

Oh this sounds super fun, thanks for the insight!