I’ve been thinking a lot about sliding scales of environment and narrative within immersive experiences.

This started a few months ago, while I was reading Margaret Kerrison’s Immersive Storytelling for Real and Imagined Worlds, a fantastic book that I have been flinging at the heads of everyone I know who’s even slightly interested in this work. Much of the book is a walkthrough of things to think about when creating an immersive experience — the Big Questions that should drive a project to produce a satisfying and transformative journey for the audience.

The piece of it that I keep chewing on is the role of the audience and how that relates to both how they experience the story and what the goal is — what you want them to think and feel, how you want them to play and engage. It’s a lot about how much agency the experience affords the audience. Here’s a very brief sketch of how Kerrison breaks down six types of audience role:

Visitor: Anyone can come and go, discovering what is laid out for them; employees are not part of the story.

Spectator: The audience is acknowledged but not participatory; there is a clean line between spectators and performers.

Participant - Immersive: The audience has freedom to explore and discover, but is largely invisible and does not interact or change the story; their actions are a light touch on the environment.

Participant - Interactive: The audience can interact with the story, characters, and environment in a larger and more meaningful way, and that action is key to the experience — but it will not change the structure or outcome.

Hero: The audience has an identity within the world (either bestowed upon them, self-invented, or a hybrid of the two -- and can evolve over course of the experience). How participants engage and react influences and can even determine the outcome (or may at least influence/determine how the outcome plays out).

Creator: The participant fully determines their story within set parameters of the world.

For more detail on those, go get the book! Or, Kerrison also talks about them in this wonderful interview.

Not long after finishing the book, I headed off to Disney World, and I found myself thinking about audience roles in various parts of the parks. If you walk into Gods of the Vikings in the Norway pavilion at EPCOT, you’re a Visitor, because that’s essentially a musuem exhibit without interactive components. When you sit down to watch Fantasmic! or hop into an Omnimover to cruise through the Haunted Mansion, you’re a Spectator. The new Journey of Water Inspired by Moana is a fabulous example of Participant-Interactive, because your action of playing with the water is key (and I would argue that the water itself is the main character in that story that you’re interacting with). Millennium Falcon: Smuggler’s Run is a fabulous innovation that puts you in the role of Hero, because the outcome does change (within certain parameters) based on how well your team pilots the ship, acquires coaxium, and makes repairs!

My head was most in this space after I visited Pandora: The World of Avatar for, really, the first time. I’d walked through it before, but I’d never done either of the rides before this first trip. Aesthetically and technologically, it’s astounding. Truly, everything is beyond beautiful. Na’Vi River Journey bioluminscent forest is like gliding peacefully through a dream, and the Shaman of Songs audio-animatronic is simply incredible. And in Flight of Passage, the ride vehicle tech is brilliant. I particularly loved that you could feel the banshee “breathing” beneath you.

In most of Pandora, your role is Spectator. You’re observing, taking in the world around you. There are a few more Participant-Immersive elements, like the way you can play with Swotu Wayä drums, but by and large, I found the experience to be gorgeous, but passive.

I couldn’t help but compare it to Galaxy’s Edge. And I recognize that I have an incredible amount of emotional investment in Star Wars and literally none in Avatar, but I don’t think that’s the only reason they feel different to me. I have friends who don’t share my Star Wars obsession but who have become absolutely engrossed in Batuu. They’re not Star Wars fans; they’re very specifically Galaxy’s Edge fans, to the extent of Batuubounding, playing sabacc, and learning new skills in order to handcraft their own accessories. Something in Galaxy’s Edge grabbed them and grabbed them hard.

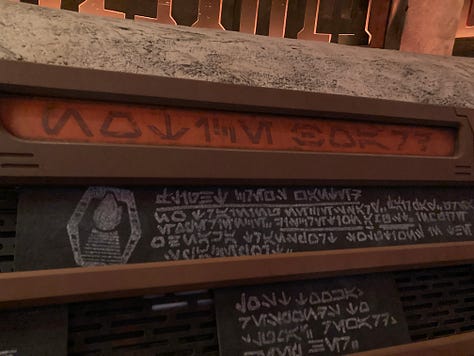

Your role in Galaxy’s Edge varies, but on balance, it’s more active — often Participant - Interactive if not downright Hero. You can, if you choose, talk to employees in-world and in-character. Both Smuggler’s Run and Rise of the Resistance have interactive components to go along with their dazzling (if, in the case of Rise, occasionally temperamental) tech. I still haven’t actually done Savi’s Workshop to build a lightsaber or the Droid Depot to assemble an astromech companion ($$$, y’all, I indulge plenty but I do still have to choose my indulgences), but those are customizable in-world experiences. Roaming characters, the Black Spire Outpost radio station, the whole vibe in Oga’s, to say nothing of the wildly interactive components of the Datapad in the Play Disney app — where your actions on your cell phone sometimes actually trigger reactions in the real world. (Go hack droids, vehicles, and comms towers when someone is standing near them; it’s fun!)

The key difference, overall, is that there’s more room for you in Galaxy’s Edge than in Pandora. You can choose to be just a Spectator, but the land invites so much more than that, in so many ways. And you are drenched in narrative in GE. Even if you don’t know what the full story is, you can tell it’s happening all around you.

(As a slight sidebar: Every area in the Disney Parks benefits from live entertainment, particularly in the form of “streetmosphere” characters. A lot of those still haven’t been brought back since the 2020 closures — but they need to be! People have more ability to create magic moments than anything else. I understand Pandora used to have some of that? Which would have created more variety of experience there.)

Okay. So how does all of this relate to environment and narrative, like I said at the beginning?

How the audience experiences the story is built of a lot of different things, but lately, I find myself thinking a lot about how those components contribute both/either to the environment and/or to the narrative. The environment is, for me, the stuff that’s about the space where the audience’s body is during the experience; the narrative is the space where their mind is. These things are not discrete; they feed into each other, and both are what build the story that the audience becomes part of. (And I recognize that attempting to delineate terms between “story” and “narrative” is a little mind-bendy, but at least for the purposes of this blog post, that’s what I’m rolling with). But there’s flexibility in how much an experience might lean into one, the other, or both — and certain kinds of audience roles require more of one or the other.

A museum need to be high-environment for Visitors and either kind of Participant, because without that environment, there’s nothing to explore. It is the space and the objects and exhibits in it (though obviously there’s a wide variety of ways to create that space).

Theatre, though, can exist on a spectrum! Some are high-environment (great current example of this is Moulin Rouge! on Broadway), but Spectators can also enjoy a show in a stripped-down black box theater; Participants-Interactive can be part of the story at a murder mystery dinner theatre inside a banquet hall or at a Renaissance faire in an open field. Some places might up the ante a little: the Blackfriars Playhouse is an environment all on its own, but the audience’s imagination is still required to turn the bare-bones stage and sparse sets into the Forest of Arden, the fields of Agincourt, Elsinore, or Dunsinane; a Renaissance faire might have some permanent structures to create a stronger atmosphere. But when the environment is low-to-medium, then the narrative must be all the more compelling to draw the audience in — and that’s about the strength of the story itself and the performers bringing it to life.

I mean, Shakespeare knew that.

Can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this great accompt,

On your imaginary forces work. […]

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts;

Into a thousand parts divide on man, […]

For 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there; jumping o'er times,

Turning the accomplishment of many years

Into an hour-glass.

—Chorus, Henry V

A lot of the most visible examples of immersive experiences are high-environment and high-narrative.

The pinnacle, for me, is the Galactic Starcruiser (shocking relevation, I know), where the audience was encouraged to take on the role of Hero: your experience varied depending on who you interacted with, how much, what affiliation you chose to embrace, and so forth. The overall outcome was still the same, still scripted — but there was flexibility in how we arrived at that outcome, and even smaller moments inside the scripted elements could change based on relationships that had developed. (Here’s one amazing example on Instagram from performer Sage Starkey, tailoring a moment to one particular participant — in a way that engaged and delighted the whole crowd!)

Across Disney World, pretty much everything is high-environment, although with some variability largely related to when an area was built or renovated. Fantasyland in the Magic Kingdom doesn’t have the “lived-in” quality you get in Africa and Asia in the Animal Kingdom or Galaxy’s Edge in Hollywood Studios, for example.

Or, to get out of the theme park world, think about something like Sleep No More. The audience role there is Participant - Immersive, very occasionally shading to Participant - Interactive — you’re free to explore, but for the most part, the performers act like you don’t exist. But it’s still both high-environment and high-narrative. That place is packed with narrative, not just Macbeth but references to all sorts of gothic weirdness. (I’ve been twice, and I’m still not quite sure what happened to me either time; it really does feel like a surreal dream).

An example of a high-environment, low-narrative experience might be something like those boutique hotels that have started offering fully themed rooms. It’s all about the theming, and it benefits from your presence, but if you leave the room, nothing about it changes. Your experience of it will be roughly the same as anyone else occupying the same space. Such rooms place the audience in the role of Participant - Immersive. You’re free to explore, uncover hidden details, etc, but your activity doesn’t change anything or further any kind of narrative.

So what about flipping those sliders to low-environment, high-narrative? The furthest points there would be things like tabletop rpgs (unless you’re playing in some themed location, but most of us are playing them in our friends’ living rooms or the backrooms of game shops — or, these days, through voice chats on Discord or Roll20 or other such platforms). The narrative is everything then, and the participants are entirely reliant on the theatre of the imagination. The audience is somewhere between Hero and Creator, depending on how their particular game runs.

Traditional-style LARPing can also be somewhere on this side of the spectrum. Certainly there are high-environment LARPs, but my sense is that the more common ones operate similarly to how we do at Mythik Camps: foam weapons in public parks, because renting & decorating venues gets expensive fast.

Something more middling on the environment slider might be a lot of the fantasy and Regency balls that have been gaining steam lately. Those tend to take over a hotel ballroom or some other space that probably spends most of its life hosting weddings and reuinons; there are scenic elements, but you’re unlikely to fully forget that you’re in a hotel. The smaller, “tent faire” style of Renaissance faires fall into this range, too — temporary structures, taking over a public park, a vineyard, or even a parking lot (I’ve worked all three at some point!) with a few visual elements as signals, but certainly not creating a full break with the realm of reality.

This balance within immersive entertainment is something I’m chewing on a lot because most of the work I’ve done has been low-environment but high-narrative.

That has often, admittedly, been a function of available budget and resources, but it also isn’t only that. Don’t get me wrong, I’d love to find out what I’d be capable of creating with Disney-level money — but there will always be something profoundly satisfying when a group of people come together and weave a heart-seizing story out of words, voice, action, emotion, intensity, and belief in the world they are co-creating. I love that this is a thing we as humans can do inside our own heads. I mean, seriously, how cool is that??

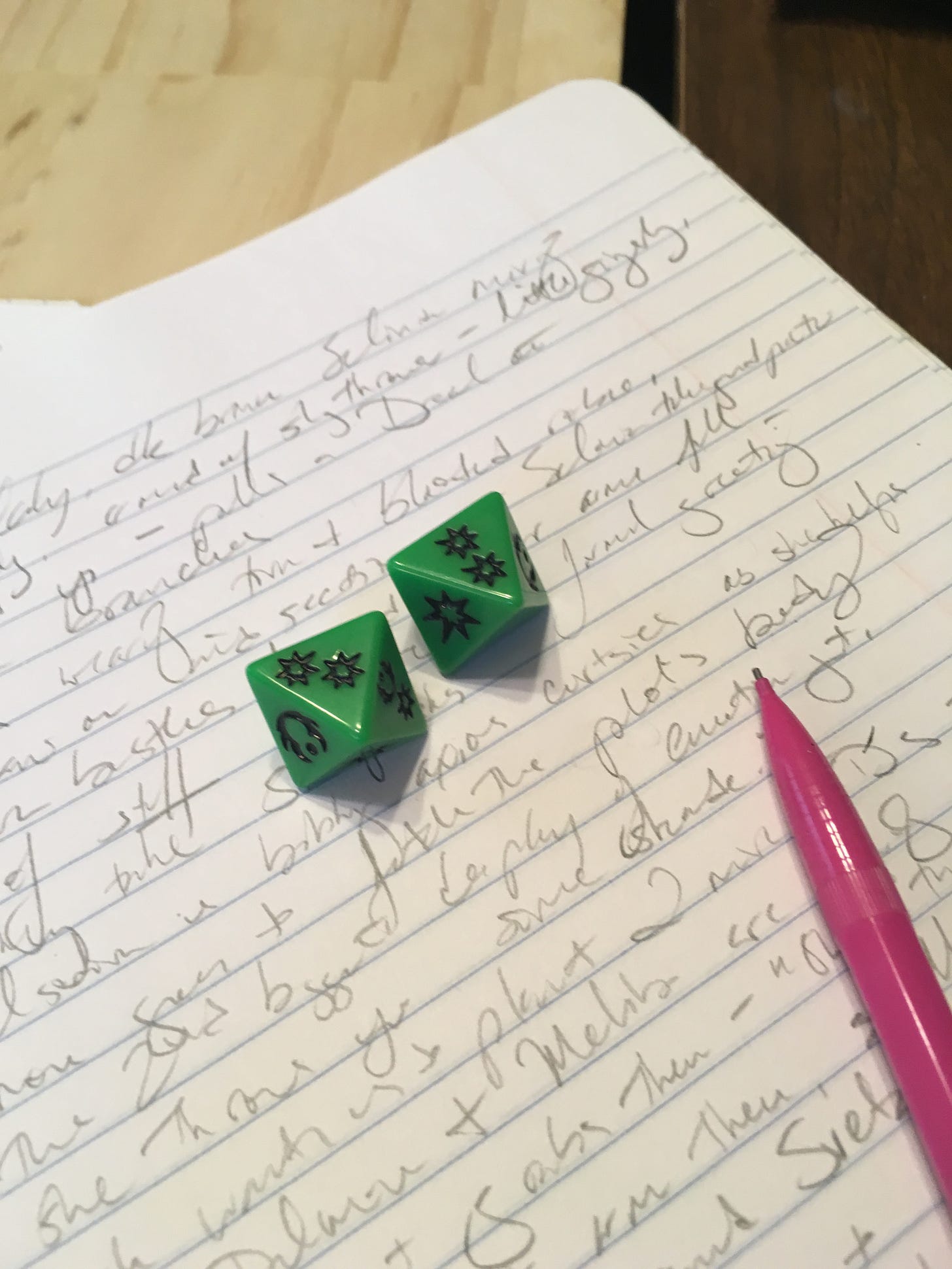

I think of the long TTRPG campaigns I’ve been in. The Star Wars: Edge of the Empire/Age of Rebellion, with our hearts in our throats, barely able to stay seated because we couldn’t contain our energy and tension over a climactic scene. We had paper, pencils, dice, a dry erase board map, and each other. Or my current game of Star Trek: Adventures, where for three straight sessions, my heart has been pounding as I’ve attempted to unravel and then negotiate Mirror-Universe-related problems. We roll dice in Discord and use voice chat, without even each others’ faces to play off of.

Very low-environment. Very, very high-narrative. Fully immersed in the story.

I love the power that imagination has.

This is something kids get, instinctively, that too many adults forget. Adults tend to need more props and trappings. Kids will turn a stick into a sword, a vial of crushed leaves and dirty water into a potion, a shadowy spot between two trees into a monster’s lair. They are much quicker to embrace Secondary Belief (which I’ve talked about before) — if the story is compelling enough.

Thus, the work of Mythik Camps is very high on narrative, but low on environment (considering we operate in public parks). We are trying to figure out practical ways to bring some more scenic elements to our camps, but that’s not the topmost priority.

Our goal is to make each of our campers a Hero. We tell prospective Quest Guides and performers that we want kids to walk away saying “I did something amazing today” not “I watched something amazing happen.”

And when they’re in, they are all-in. I will never forget, in my first season, a beat where I got “drained of my power” to illustrate the strength of the antagonist’s weapon. I did this with four different groups, with differing levels of buy-in, but in one of them, when I collapsed, one of the campers shrieked “CASS IS DEAD!!!” and had to be restrained from charging off into the woods to maim the performer who had “attacked” me. She was very relieved when I did, in fact, recover, but she kept checking on me all day. And this was a ten-year-old who very much knew how it all worked, because she was already asking me how old she would have to be to become a performer with us. But she chose to go all-in — with a foam sword, on a park path, with the fishing and mountain biking clubs occasionally passing by us.

So why does this matter? Why is it something I’ve nattered on about for a couple thousand words?

I care about this distinction because I don’t like the implication that an experience has to be high-environment to be considered immersive, even though that’s becoming the assumption attached to the phrase. When people say “immersive”, they tend to mean “immersive environment” — but “immersive theater” or “immersive event” might or might not be heavily dependent on the environment. They’re not all synonymous; I think of them as all inter-related components of things under the greater umbrella of “immersive experiences”. The mental and emotional immersion, driven by the narrative, are also important and can be attained even if you don’t have a space you can customize, the money to do so, or access to high tech tools and toys.

A high-environment experience is, I think, less likely to be transformative if it’s too low on the narrative scale. It might be beautiful, impressive, interesting — but I don’t think it reaches in and grips your heart in quite the same way.

Put another way: With a strong enough narrative, I can make you the Hero, no matter the environment. But a super-strong environment won’t make you the Hero without a strong narrative.

(Mind you, if what you’ve promised is a high-environment experience, you’d best deliver on it; none of us want to be sad Wonkas. That’s why we expend effort at Mythik Camps making sure we’re not over-promising in our marketing materials!)

I care about this because it’s worth exploring how we can make the high-narrative low-environment experiences better and better, because those have the potential to be accessible to more people. You shouldn’t have to be in one of a few major cities, where the high-environment experiences tend to be, in order to have a powerful immersive experience.

Yes, there are TTRPGs and LARPs available all over the place, but those can have a high barrier of entry of a different kind — finding the right group, dealing with cliqueishness and insularity, not to mention the difficulties of scheduling an ongoing commitment. I want to see more events and experiences that are easy to find, easy to join, lower-time-investments, but which are still powerful, inspirational, transformative.

Anyway, this is one of the things I’ve been thinking about as I analyze my own work in comparison to other forms of immersive experiences. More to come!